-

1842 - 1844

-

Institut Frenopàtic de Les Corts

Inicialment era el sanatori dels Doctors Dolsa i Llorach. El Doctor Pau Llorach era el propietari dels terrenys. Malgrat es desconeix el projecte i la data de la seva construcció, el 1863 el sanatori ja funcionava, i a l'any 1867 consta com a limítrof de les terres de Vicenç Cuyás i Barberá, qui en fa esment en redactar en aquest any el seu testament. La construcció es basava en els principis preconitzats per Samuel Tuke a Anglaterra el segle XVIII: integració de la naturalesa aprofitant sobretot els boscs, i enjardinaments amb elements constructius, com ara estanys o cascades. De la construcció original del Frenopàtic de les Corts realitzat a principis de la dècada dels seixanta del segle XIX s'ha conservat la façana principal. Aquesta presenta una composició axial, arrelada en el neoclassicisme, a partir de la capella central, que separa les zones de homes i dones. Aquestes conserven en un frontó situat al damunt dels seus accessos els rètols “departamento de caballeros” i el “departamento de señoras”. En alçat s'ha conservat la seva volumetria original, amb dos plantes, la segona on les obertures presenten balconades amb balustrada. La teulada es presenta a doble vessant. També s'ha conservat un casalot residencial de volum compacte, dos plantes d'alçada i coberta de pavelló situat a la cantonada del carrer Mejía Lequerica i la gran via de Carles III, a la zona de jardí tancat per una reixa de ferro.

Inicialment era el sanatori dels Doctors Dolsa i Llorach. El Doctor Pau Llorach era el propietari dels terrenys. Malgrat es desconeix el projecte i la data de la seva construcció, el 1863 el sanatori ja funcionava, i a l'any 1867 consta com a limítrof de les terres de Vicenç Cuyás i Barberá, qui en fa esment en redactar en aquest any el seu testament. La construcció es basava en els principis preconitzats per Samuel Tuke a Anglaterra el segle XVIII: integració de la naturalesa aprofitant sobretot els boscs, i enjardinaments amb elements constructius, com ara estanys o cascades. De la construcció original del Frenopàtic de les Corts realitzat a principis de la dècada dels seixanta del segle XIX s'ha conservat la façana principal. Aquesta presenta una composició axial, arrelada en el neoclassicisme, a partir de la capella central, que separa les zones de homes i dones. Aquestes conserven en un frontó situat al damunt dels seus accessos els rètols “departamento de caballeros” i el “departamento de señoras”. En alçat s'ha conservat la seva volumetria original, amb dos plantes, la segona on les obertures presenten balconades amb balustrada. La teulada es presenta a doble vessant. També s'ha conservat un casalot residencial de volum compacte, dos plantes d'alçada i coberta de pavelló situat a la cantonada del carrer Mejía Lequerica i la gran via de Carles III, a la zona de jardí tancat per una reixa de ferro.1872 - 1883

-

1892

-

1893 - 1895

-

1883 - 1898

-

Provincial Maternity Home (Avemaria Pavilion)

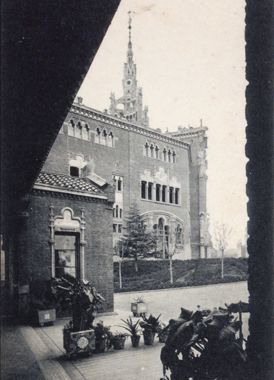

Located in the district of Les Corts, the complex known as Casa Provincial de Maternitat is located on the block of houses bounded by Travessera de Les Corts and Carrer de la Maternitat, Doctor Salvador Cardenal and Mejía Lequerica Streets. The main access to the complex is from Travessera de Les Corts. The complex is made up of a large group of pavilions built in different phases and distributed within a large, enclosed area. The original core of buildings, located at the southern end of the plot, is composed of five pavilions arranged around a large rectangular courtyard. These buildings have a height development consisting of a semi-basement, two floors and attics. They show a clear compositional unity and general arrangement, with a unique treatment of façades and a game of textures achieved by mixing exposed brick with stone walls. While the plinths of the buildings are made of regular stone blocks placed at break-joints, on the other levels the work is of common masonry. These textures are separated at the level of the slabs by rows of work with a slight overhang, where polychrome ceramic friezes stand out along the entire perimeter of the building. The crowning consists of a barbican that goes around the entire perimeter simulating a defensive enclosure. The constructions started during the period of the Mancomunitat, meaning that the Pink and Blue Pavilions were designed by Josep Goday i Casals in a style closer to Noucentisme. The Pink Pavilion recovers the characteristic motifs of the Catalan Baroque, with the inclusion of sgraffitos (geometrising borders and baskets) and terracottas. The putti and the shield of the main door solved in the form of a shell were done by Canyellas, and the crowning is based on balusters and vases. The Blue Pavilion has earth-coloured sgraffito coverings on its façades; it received its name from the name of the glazed ceramic dome that crowns the central body. The Pavilion of Helios represents a turning point, bringing to the whole a building within the rationalist current of the GATCPAC. Founded in 1853, the Casa Provincial de Maternitat i Expòsits was originally located in the Casa de Misericordia (Carrer Montalegre), in the old town. With the hygienist currents of the moment, the City Council decided to improve the conditions of the institution by promoting the construction of buildings suitable for its sanitary function. For this purpose, in 1878 they acquired the Can Cavaller country house, in Les Corts. The architect of the City Council, Camil Oliveras i Gensana, together with the architects General Guitart i Lostaló and Josep Bru, designed the Lactation Pavilion, the two Infectious Pavilions and the Laundry between 1885 and 1889. In 1920, the transfer of powers of the charity services between the City Council and the Mancomunitat took place. The construction plans, which until then had been carried out by the institution, basically concerned the orphanage section, so Josep Bori drew up an ambitious project for the maternity section that should be developed on the land located to the north of the site. In 1915, the construction of the Pink Pavilion began, started by Rubí i Bellver and completed in 1924 by Josep Goday, intended to accommodate secret pregnancies or unmarried mothers. Between 1928 and 1942, the same architect built the Blue Pavilion, destined for the Maternity Clinic. Between 1933 and 1936, Goday built the Helios Pavilion, intended for children with tuberculosis, following the structural and aesthetic guidelines of GATCPAC's rationalism. After the Spanish Civil War, the institution lost the progressive and renewing attitude of the previous dynamic period and returned to being governed by the traditional concept of Christian charity, abandoning the concept of modern public service. In this context, the economy of the institution was very precarious and the construction of a new pavilion for children aged 2 to 3 could only be carried out thanks to the legacy of two million pesetas by Francesc Cambó i Batlle. The architect Manuel Baldrich i Tibau oversaw its construction between 1953 and 1957. With the start of work on the Llars Mundet in 1954 and seeing that the buildings of the Maternity Hospital were no longer suitable for the social needs of the moment, the Council began to reconsider the uses of the site. Finally, in 1985, the Action and Planning Plan for the Maternity Home was approved, drawn up by the architects Josep Lluís Canosa and Carles Ferrater. This document laid the foundations for converting the existing buildings into public buildings intended for equipment and services, concentrating all hospital services in the Blue Pavilion and turning the outdoor spaces into a park. Currently, the Lactation pavilion is occupied by the Consortium of Resources for the Integration of Diversity (CRID), the Tourism Delegation, the Area of Economic Promotion and Employment and the Tax Management Organization (ORGT); the Pavelló de Desmamats is the seat of the Ministry of Health of the Generalitat of Catalonia; in the old infectious disease pavilions there is the Directorate of Urban Planning and Housing Services, the Institute of Urban Management and Local Activities (IGUAL) and the Institute of Local Housing (INHAL); the Historical Archive of the Barcelona City Council was installed in the Laundry; the headquarters of the Distance Education University (UNED) was installed in the Pavilion of the Kitchens; the Pink Pavilion would cease to fulfill its function in 1974 and, fifteen years later, would host the offices of COOB'92. The Blue Pavilion has hosted, since 1993, the Hospital Clínic Health Consortium; the Cambó Pavilion has been home to the Jordi Rubió i Balaguer University School of Library Science since 1991; and since 1989, the Prat de la Riba Pavilion has been home to Les Corts Secondary School.

Located in the district of Les Corts, the complex known as Casa Provincial de Maternitat is located on the block of houses bounded by Travessera de Les Corts and Carrer de la Maternitat, Doctor Salvador Cardenal and Mejía Lequerica Streets. The main access to the complex is from Travessera de Les Corts. The complex is made up of a large group of pavilions built in different phases and distributed within a large, enclosed area. The original core of buildings, located at the southern end of the plot, is composed of five pavilions arranged around a large rectangular courtyard. These buildings have a height development consisting of a semi-basement, two floors and attics. They show a clear compositional unity and general arrangement, with a unique treatment of façades and a game of textures achieved by mixing exposed brick with stone walls. While the plinths of the buildings are made of regular stone blocks placed at break-joints, on the other levels the work is of common masonry. These textures are separated at the level of the slabs by rows of work with a slight overhang, where polychrome ceramic friezes stand out along the entire perimeter of the building. The crowning consists of a barbican that goes around the entire perimeter simulating a defensive enclosure. The constructions started during the period of the Mancomunitat, meaning that the Pink and Blue Pavilions were designed by Josep Goday i Casals in a style closer to Noucentisme. The Pink Pavilion recovers the characteristic motifs of the Catalan Baroque, with the inclusion of sgraffitos (geometrising borders and baskets) and terracottas. The putti and the shield of the main door solved in the form of a shell were done by Canyellas, and the crowning is based on balusters and vases. The Blue Pavilion has earth-coloured sgraffito coverings on its façades; it received its name from the name of the glazed ceramic dome that crowns the central body. The Pavilion of Helios represents a turning point, bringing to the whole a building within the rationalist current of the GATCPAC. Founded in 1853, the Casa Provincial de Maternitat i Expòsits was originally located in the Casa de Misericordia (Carrer Montalegre), in the old town. With the hygienist currents of the moment, the City Council decided to improve the conditions of the institution by promoting the construction of buildings suitable for its sanitary function. For this purpose, in 1878 they acquired the Can Cavaller country house, in Les Corts. The architect of the City Council, Camil Oliveras i Gensana, together with the architects General Guitart i Lostaló and Josep Bru, designed the Lactation Pavilion, the two Infectious Pavilions and the Laundry between 1885 and 1889. In 1920, the transfer of powers of the charity services between the City Council and the Mancomunitat took place. The construction plans, which until then had been carried out by the institution, basically concerned the orphanage section, so Josep Bori drew up an ambitious project for the maternity section that should be developed on the land located to the north of the site. In 1915, the construction of the Pink Pavilion began, started by Rubí i Bellver and completed in 1924 by Josep Goday, intended to accommodate secret pregnancies or unmarried mothers. Between 1928 and 1942, the same architect built the Blue Pavilion, destined for the Maternity Clinic. Between 1933 and 1936, Goday built the Helios Pavilion, intended for children with tuberculosis, following the structural and aesthetic guidelines of GATCPAC's rationalism. After the Spanish Civil War, the institution lost the progressive and renewing attitude of the previous dynamic period and returned to being governed by the traditional concept of Christian charity, abandoning the concept of modern public service. In this context, the economy of the institution was very precarious and the construction of a new pavilion for children aged 2 to 3 could only be carried out thanks to the legacy of two million pesetas by Francesc Cambó i Batlle. The architect Manuel Baldrich i Tibau oversaw its construction between 1953 and 1957. With the start of work on the Llars Mundet in 1954 and seeing that the buildings of the Maternity Hospital were no longer suitable for the social needs of the moment, the Council began to reconsider the uses of the site. Finally, in 1985, the Action and Planning Plan for the Maternity Home was approved, drawn up by the architects Josep Lluís Canosa and Carles Ferrater. This document laid the foundations for converting the existing buildings into public buildings intended for equipment and services, concentrating all hospital services in the Blue Pavilion and turning the outdoor spaces into a park. Currently, the Lactation pavilion is occupied by the Consortium of Resources for the Integration of Diversity (CRID), the Tourism Delegation, the Area of Economic Promotion and Employment and the Tax Management Organization (ORGT); the Pavelló de Desmamats is the seat of the Ministry of Health of the Generalitat of Catalonia; in the old infectious disease pavilions there is the Directorate of Urban Planning and Housing Services, the Institute of Urban Management and Local Activities (IGUAL) and the Institute of Local Housing (INHAL); the Historical Archive of the Barcelona City Council was installed in the Laundry; the headquarters of the Distance Education University (UNED) was installed in the Pavilion of the Kitchens; the Pink Pavilion would cease to fulfill its function in 1974 and, fifteen years later, would host the offices of COOB'92. The Blue Pavilion has hosted, since 1993, the Hospital Clínic Health Consortium; the Cambó Pavilion has been home to the Jordi Rubió i Balaguer University School of Library Science since 1991; and since 1989, the Prat de la Riba Pavilion has been home to Les Corts Secondary School. -

Casa Provincial de Maternitat Hospital (Former Breastfeeding Pavilion)

Located in the district of Les Corts, the complex known as Casa Provincial de Maternitat is located on the block of houses bounded by Travessera de Les Corts and Maternitat, Doctor Salvador Cardenal and Mejía Lequerica Streets. The main access to the complex is from Travessera de Les Corts. The complex is made up of a large group of pavilions built in different phases and distributed within a large, enclosed area. The original core of buildings, located at the southern end of the plot, is composed of five pavilions arranged around a large rectangular courtyard. These buildings have a height development consisting of a semi-basement, two floors and attics. They show a clear compositional unity and general arrangement, with a unique treatment of façades and the interplay of textures achieved by mixing exposed brick with stone walls. While on the plinths of the buildings the device is made of regular stone blocks placed at break joints, on the other levels the work is of common masonry. These textures are separated at the level of the slabs by rows of work with a slight overhang, where polychrome ceramic friezes stand out along the entire perimeter of the building. The crowning consists of a barbican that goes around the entire perimeter simulating a defensive enclosure. The constructions started during the period of the Mancomunitat; so, the Pink and Blue Pavilions, were designed by Josep Goday and Casals in a style closer to Noucentisme. The Pink Pavilion recovers the characteristic motifs of the Catalan Baroque, with the inclusion of sgraffitos (geometrising borders and baskets) and terracottas. The putti and the shield of the main door solved in the form of a shell were done by Canyellas, while the crowning is based on balusters and vases. The Blue Pavilion has earth-coloured sgraffito coverings on its façades; it got its name from the name of the glazed ceramic dome that crowns the central body. The Pavilion of Helios represents a turning point, bringing to the whole a building within the rationalist trend of the GATCPAC. Founded in 1853, the Provincial Maternity and Exhibition Centre was originally located in the Casa de Misericordia (Carrer Montalegre), in the old town. With the hygienist currents of the moment, the city council decided to improve the conditions of the institution by promoting the construction of buildings suitable for its sanitary function. For this purpose, in 1878 it acquired the farmhouse of Can Cavaller, in Les Corts. The architect of the Provincial Council, Camil Oliveras i Gensana, together with the architects General Guitart i Lostaló and Josep Bru, designed between 1885 and 1889 the Lactation Pavilion, the Weanling Pavilion, the two Infectious Pavilions and the Laundry. In 1920, the transfer of powers of the charity services between the Provincial Council and the Mancomunitat took place. The construction plans, which until then had been carried out by the institution, basically concerned the exhibition section, so Josep Bori drew up an ambitious project for the maternity section that should be developed on the land located to the north of the site. In 1915, the construction of the Pink Pavilion began, started by Rubí i Bellver and completed in 1924 by Josep Goday, intended to accommodate secret pregnancies or unmarried mothers. Between 1928 and 1942, the same architect built the Blue Pavilion, destined for the Maternity Clinic. Between 1933 and 1936, Goday built the Helios Pavilion, intended for tuberculosis children, following the structural and aesthetic guidelines of GATCPAC's own rationalism. After the Civil War, the institution lost the progressive and renewing attitude of the previous dynamic period and returned to being governed by the traditional concept of Christian charity, abandoning the concept of modern public service. In this context, the economy of the institution was very precarious and the construction of a new pavilion for children aged 2 to 3 could only be carried out thanks to the legacy of two million pesetas by Francesc Cambó i Batlle. The architect Manuel Baldrich i Tibau oversaw its construction between 1953 and 1957. With the start of work on the Mundet Apartments in 1954 and seeing that the buildings of the Maternity Hospital were no longer suitable for the social needs of the moment, the Council began to reconsider the uses of the site. Finally, in 1985, the Action and Planning Plan for the Maternity Home was approved, drawn up by the architects Josep Lluís Canosa and Carles Ferrater. This document laid the foundations for converting the existing buildings into public buildings intended for equipment and services, concentrating all hospital services in the Blue Pavilion and turning the outdoor spaces into a park. Currently, the Lactation pavilion is occupied by the Consortium of Resources for the Integration of Diversity (CRID), the Tourism Delegation, the Area of Economic Promotion and Employment and the Tax Management Organization (ORGT); the Weanling Pavilion is now the seat of the Ministry of Health of the Generalitat of Catalonia; in the former infectious disease pavilions there is the Directorate of Urban Planning and Housing Services, the Institute of Urban Management and Local Activities (IGUAL) and the Institute of Local Housing (INHAL); the Historical Archive of the Barcelona City Council was installed in the Laundry; the headquarters of the Distance Education University (UNED) was installed in the Pavilion of the Kitchens; the Pink Pavilion would cease to fulfill its function in 1974 and, fifteen years later, would host the offices of the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games. The Blue Pavilion has hosted, since 1993, the Hospital Clínic Health Consortium; the Pavilion Cambó has been home to the Jordi Rubió i Balaguer University School of Library Science since 1991; and since 1989, the Prat de la Riba Pavilion has been home to the Les Corts Secondary School.

Located in the district of Les Corts, the complex known as Casa Provincial de Maternitat is located on the block of houses bounded by Travessera de Les Corts and Maternitat, Doctor Salvador Cardenal and Mejía Lequerica Streets. The main access to the complex is from Travessera de Les Corts. The complex is made up of a large group of pavilions built in different phases and distributed within a large, enclosed area. The original core of buildings, located at the southern end of the plot, is composed of five pavilions arranged around a large rectangular courtyard. These buildings have a height development consisting of a semi-basement, two floors and attics. They show a clear compositional unity and general arrangement, with a unique treatment of façades and the interplay of textures achieved by mixing exposed brick with stone walls. While on the plinths of the buildings the device is made of regular stone blocks placed at break joints, on the other levels the work is of common masonry. These textures are separated at the level of the slabs by rows of work with a slight overhang, where polychrome ceramic friezes stand out along the entire perimeter of the building. The crowning consists of a barbican that goes around the entire perimeter simulating a defensive enclosure. The constructions started during the period of the Mancomunitat; so, the Pink and Blue Pavilions, were designed by Josep Goday and Casals in a style closer to Noucentisme. The Pink Pavilion recovers the characteristic motifs of the Catalan Baroque, with the inclusion of sgraffitos (geometrising borders and baskets) and terracottas. The putti and the shield of the main door solved in the form of a shell were done by Canyellas, while the crowning is based on balusters and vases. The Blue Pavilion has earth-coloured sgraffito coverings on its façades; it got its name from the name of the glazed ceramic dome that crowns the central body. The Pavilion of Helios represents a turning point, bringing to the whole a building within the rationalist trend of the GATCPAC. Founded in 1853, the Provincial Maternity and Exhibition Centre was originally located in the Casa de Misericordia (Carrer Montalegre), in the old town. With the hygienist currents of the moment, the city council decided to improve the conditions of the institution by promoting the construction of buildings suitable for its sanitary function. For this purpose, in 1878 it acquired the farmhouse of Can Cavaller, in Les Corts. The architect of the Provincial Council, Camil Oliveras i Gensana, together with the architects General Guitart i Lostaló and Josep Bru, designed between 1885 and 1889 the Lactation Pavilion, the Weanling Pavilion, the two Infectious Pavilions and the Laundry. In 1920, the transfer of powers of the charity services between the Provincial Council and the Mancomunitat took place. The construction plans, which until then had been carried out by the institution, basically concerned the exhibition section, so Josep Bori drew up an ambitious project for the maternity section that should be developed on the land located to the north of the site. In 1915, the construction of the Pink Pavilion began, started by Rubí i Bellver and completed in 1924 by Josep Goday, intended to accommodate secret pregnancies or unmarried mothers. Between 1928 and 1942, the same architect built the Blue Pavilion, destined for the Maternity Clinic. Between 1933 and 1936, Goday built the Helios Pavilion, intended for tuberculosis children, following the structural and aesthetic guidelines of GATCPAC's own rationalism. After the Civil War, the institution lost the progressive and renewing attitude of the previous dynamic period and returned to being governed by the traditional concept of Christian charity, abandoning the concept of modern public service. In this context, the economy of the institution was very precarious and the construction of a new pavilion for children aged 2 to 3 could only be carried out thanks to the legacy of two million pesetas by Francesc Cambó i Batlle. The architect Manuel Baldrich i Tibau oversaw its construction between 1953 and 1957. With the start of work on the Mundet Apartments in 1954 and seeing that the buildings of the Maternity Hospital were no longer suitable for the social needs of the moment, the Council began to reconsider the uses of the site. Finally, in 1985, the Action and Planning Plan for the Maternity Home was approved, drawn up by the architects Josep Lluís Canosa and Carles Ferrater. This document laid the foundations for converting the existing buildings into public buildings intended for equipment and services, concentrating all hospital services in the Blue Pavilion and turning the outdoor spaces into a park. Currently, the Lactation pavilion is occupied by the Consortium of Resources for the Integration of Diversity (CRID), the Tourism Delegation, the Area of Economic Promotion and Employment and the Tax Management Organization (ORGT); the Weanling Pavilion is now the seat of the Ministry of Health of the Generalitat of Catalonia; in the former infectious disease pavilions there is the Directorate of Urban Planning and Housing Services, the Institute of Urban Management and Local Activities (IGUAL) and the Institute of Local Housing (INHAL); the Historical Archive of the Barcelona City Council was installed in the Laundry; the headquarters of the Distance Education University (UNED) was installed in the Pavilion of the Kitchens; the Pink Pavilion would cease to fulfill its function in 1974 and, fifteen years later, would host the offices of the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games. The Blue Pavilion has hosted, since 1993, the Hospital Clínic Health Consortium; the Pavilion Cambó has been home to the Jordi Rubió i Balaguer University School of Library Science since 1991; and since 1989, the Prat de la Riba Pavilion has been home to the Les Corts Secondary School. -

Sant Josep and Sant Pere Hospital and Asylum

The complex takes up the entire block between the streets of Jacas, Marañón, Maragall and Claret. It is an isolated building, with a complex organisation, formed by two bodies arranged perpendicular to another central body. It includes several outbuildings, including a chapel and a battlemented tower. The roofs are generally two-sided tiles. The construction has openings of various typologies that are framed in brick. There are several entrances to the building, which is surrounded by a garden. At the back, the shelter of Sant Josep has been the subject of several expansion works. The Sant Josep and Sant Pere asylum was built in 1901, according to a project by the architect Josep Font i Gumà. In the Historical Archive of Ribes, there is a document dated 1947, the request to the City Council for works to expand the building, in accordance with the plans signed by the architect Josep Brugal i Fortuny.

The complex takes up the entire block between the streets of Jacas, Marañón, Maragall and Claret. It is an isolated building, with a complex organisation, formed by two bodies arranged perpendicular to another central body. It includes several outbuildings, including a chapel and a battlemented tower. The roofs are generally two-sided tiles. The construction has openings of various typologies that are framed in brick. There are several entrances to the building, which is surrounded by a garden. At the back, the shelter of Sant Josep has been the subject of several expansion works. The Sant Josep and Sant Pere asylum was built in 1901, according to a project by the architect Josep Font i Gumà. In the Historical Archive of Ribes, there is a document dated 1947, the request to the City Council for works to expand the building, in accordance with the plans signed by the architect Josep Brugal i Fortuny.1901

-

1898 - 1902

-

Charity House

Religious building made up of two parts. On the one hand, the front part, where the entrance is located, in the form of a square tower crowned by a four-sided dome covered with ceramics. On the other hand, the back part, has a rectangular plan covered by a gable roof and with large side windows. All the ornamental elements that make up the ensemble are located in a neo-Gothic and eclectic tradition: bipartite windows with a column and Gothic tracery, trefoils and mouldings that serve as ogival-shaped dust guards, semicircular arches and attached columns with Corinthian capitals. The facings are of red bricks with white stuccoed recesses in the corners and framing the openings in the fashion of false arches. Access is via a staircase presided over by an ogival portal where you can read Casa Benèfica, on top of the year 1901 and a double window. There are many subsequent annexes suitable for the specific needs of the moment. Despite the construction dates given by Gaietà Buigas, 1901 is written on the façade.

Religious building made up of two parts. On the one hand, the front part, where the entrance is located, in the form of a square tower crowned by a four-sided dome covered with ceramics. On the other hand, the back part, has a rectangular plan covered by a gable roof and with large side windows. All the ornamental elements that make up the ensemble are located in a neo-Gothic and eclectic tradition: bipartite windows with a column and Gothic tracery, trefoils and mouldings that serve as ogival-shaped dust guards, semicircular arches and attached columns with Corinthian capitals. The facings are of red bricks with white stuccoed recesses in the corners and framing the openings in the fashion of false arches. Access is via a staircase presided over by an ogival portal where you can read Casa Benèfica, on top of the year 1901 and a double window. There are many subsequent annexes suitable for the specific needs of the moment. Despite the construction dates given by Gaietà Buigas, 1901 is written on the façade.1901 - 1902

-

1903 - 1905

-

1905

-

1910

-

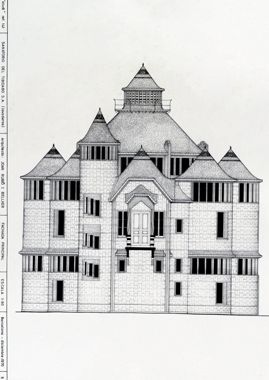

Project of the Integrated Hospitals of Santa Creu and Sant Pau

The Project of Reunited Hospitals of the Santa Creu and Sant Pau, designed by architect Lluís Domènech i Montaner, stands as one of the most ambitious and innovative hospital complexes of its time. The origin of the project dates back to the need for a new hospital for the Santa Creu, which by the late 19th century was outdated and located in a densely urbanized area, and to the legacy of Pau Gil to build the Hospital de Sant Pau. Its final realization was the result of an agreement between the Santa Creu Administration and the executors of Gil’s estate in the early 20th century. Domènech i Montaner began the project in 1901 and distinguished himself for his thorough research into the most advanced technical and sanitary innovations of the era. The architect studied 240 hospitals from around the world and incorporated the most innovative solutions into the design of the complex, especially those related to hygiene, natural light, and ventilation. The result of this approach was a monumental hospital complex spanning 13.2 hectares, with capacity for 1,000 patients, structured around a model of isolated pavilions that allowed for the separation of services and patients based on disease type and gender. This typology, inspired by German hospitals, offered significant advantages in terms of hygiene and infection control, and Domènech adapted it with his own innovative elements, such as underground galleries connecting the pavilions, allowing for the transport of materials without interfering with patient circuits. The nursing pavilions, arranged regularly and oriented east to west to optimize sunlight exposure, featured spacious, well-ventilated areas with high-ceilinged wards and natural light. These buildings included elements such as circular day rooms to facilitate disinfection and independent water towers to reduce the risk of contamination, in line with the hygienist principles that shaped hospital architecture at the time. Domènech also placed key importance on the general layout of the site, which was structured around two large central avenues crossing the complex diagonally, clearly separating the male and female sectors and the areas for infectious and non-infectious diseases. The service and specialty pavilions were arranged along the perimeter of the complex, allowing direct access for staff and materials from outside, avoiding passage through areas designated for patients. This solution not only improved operational efficiency but also provided a clearly hierarchical and functional design adapted to the needs of healthcare activities. The complex also presented a clear monumental and symbolic intent. Domènech designed the Administration Pavilion as the entrance gateway to the site, with a monumental façade and a 57-meter clock tower, and envisioned a majestic three-nave church, along with auxiliary spaces with specific functions (gas and electricity plants, laundries, workshops, etc.) that ensured the complex’s self-sufficiency. All these elements were designed with an architectural language of great decorative richness, yet always subordinated to functionality. Overall, the Project of Reunited Hospitals of the Santa Creu and Sant Pau is a masterpiece that synthesizes the sanitary and architectural advances of its time, with an integrative vision combining architecture, urban planning, engineering, and art. The result not only marked a before and after in the conception of hospitals but also established an international benchmark in modernist architecture applied to the healthcare sector.

The Project of Reunited Hospitals of the Santa Creu and Sant Pau, designed by architect Lluís Domènech i Montaner, stands as one of the most ambitious and innovative hospital complexes of its time. The origin of the project dates back to the need for a new hospital for the Santa Creu, which by the late 19th century was outdated and located in a densely urbanized area, and to the legacy of Pau Gil to build the Hospital de Sant Pau. Its final realization was the result of an agreement between the Santa Creu Administration and the executors of Gil’s estate in the early 20th century. Domènech i Montaner began the project in 1901 and distinguished himself for his thorough research into the most advanced technical and sanitary innovations of the era. The architect studied 240 hospitals from around the world and incorporated the most innovative solutions into the design of the complex, especially those related to hygiene, natural light, and ventilation. The result of this approach was a monumental hospital complex spanning 13.2 hectares, with capacity for 1,000 patients, structured around a model of isolated pavilions that allowed for the separation of services and patients based on disease type and gender. This typology, inspired by German hospitals, offered significant advantages in terms of hygiene and infection control, and Domènech adapted it with his own innovative elements, such as underground galleries connecting the pavilions, allowing for the transport of materials without interfering with patient circuits. The nursing pavilions, arranged regularly and oriented east to west to optimize sunlight exposure, featured spacious, well-ventilated areas with high-ceilinged wards and natural light. These buildings included elements such as circular day rooms to facilitate disinfection and independent water towers to reduce the risk of contamination, in line with the hygienist principles that shaped hospital architecture at the time. Domènech also placed key importance on the general layout of the site, which was structured around two large central avenues crossing the complex diagonally, clearly separating the male and female sectors and the areas for infectious and non-infectious diseases. The service and specialty pavilions were arranged along the perimeter of the complex, allowing direct access for staff and materials from outside, avoiding passage through areas designated for patients. This solution not only improved operational efficiency but also provided a clearly hierarchical and functional design adapted to the needs of healthcare activities. The complex also presented a clear monumental and symbolic intent. Domènech designed the Administration Pavilion as the entrance gateway to the site, with a monumental façade and a 57-meter clock tower, and envisioned a majestic three-nave church, along with auxiliary spaces with specific functions (gas and electricity plants, laundries, workshops, etc.) that ensured the complex’s self-sufficiency. All these elements were designed with an architectural language of great decorative richness, yet always subordinated to functionality. Overall, the Project of Reunited Hospitals of the Santa Creu and Sant Pau is a masterpiece that synthesizes the sanitary and architectural advances of its time, with an integrative vision combining architecture, urban planning, engineering, and art. The result not only marked a before and after in the conception of hospitals but also established an international benchmark in modernist architecture applied to the healthcare sector.1901 - 1911

-

1902 - 1912

-

Santa Apol·lònia Pavilion of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau

The Santa Apol·lònia Pavilion at the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner, is one of the two observation pavilions built during the first phase of the modernist project, funded by the legacy of Pau Gil. Located in the women’s sector, behind the Administration Pavilion, which was the main entrance to the site, the building was conceived to disinfect, isolate, and observe patients before transferring them to a nursing pavilion, with special attention to detecting infectious diseases. Smaller in size than the other nursing pavilions, it consisted of a single storey with direct access from the gardens. The main body housed four individual rooms arranged along an open gallery that provided natural light and ventilation. At the ends, the lateral sections contained, on one side, a small kitchen and the room for the nursing sister and, on the other, a bathroom and space for cleaning equipment. During construction, Domènech changed its orientation, rotating it 180 degrees from the original project plan so that the entrance would face the interior of the complex and integrate better into the general circulation. The exterior decoration stands out for the high-quality ceramic mosaics that adorn the side façades, depicting Saint Apollonia (originally Saint Madrona) and Saint Eulalia, created by Mario Maragliano. The pavilion, which initially bore the name of Saint Madrona, adopted its current dedication in 1957. Over time, its original function was altered and the building was repurposed for other uses. Today it forms part of the heritage complex declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is a unique example of Domènech’s ability to combine functionality and modernist beauty.

The Santa Apol·lònia Pavilion at the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner, is one of the two observation pavilions built during the first phase of the modernist project, funded by the legacy of Pau Gil. Located in the women’s sector, behind the Administration Pavilion, which was the main entrance to the site, the building was conceived to disinfect, isolate, and observe patients before transferring them to a nursing pavilion, with special attention to detecting infectious diseases. Smaller in size than the other nursing pavilions, it consisted of a single storey with direct access from the gardens. The main body housed four individual rooms arranged along an open gallery that provided natural light and ventilation. At the ends, the lateral sections contained, on one side, a small kitchen and the room for the nursing sister and, on the other, a bathroom and space for cleaning equipment. During construction, Domènech changed its orientation, rotating it 180 degrees from the original project plan so that the entrance would face the interior of the complex and integrate better into the general circulation. The exterior decoration stands out for the high-quality ceramic mosaics that adorn the side façades, depicting Saint Apollonia (originally Saint Madrona) and Saint Eulalia, created by Mario Maragliano. The pavilion, which initially bore the name of Saint Madrona, adopted its current dedication in 1957. Over time, its original function was altered and the building was repurposed for other uses. Today it forms part of the heritage complex declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is a unique example of Domènech’s ability to combine functionality and modernist beauty. -

Sant Jordi Pavilion of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau

The Sant Jordi Pavilion of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner, is one of the two observation pavilions built during the first phase of the modernist project, funded by Pau Gil’s legacy. Located in the men’s sector, behind the Administration Pavilion, where the complex was accessed, the building was conceived to disinfect, isolate, and observe patients before they were transferred to a nursing pavilion, with special attention to the detection of infectious diseases. Smaller in size than the other nursing pavilions, it had a single floor with direct access from the gardens. The main body contained four individual rooms arranged along an open gallery that ensured natural light and ventilation. At the ends, the side wings housed, on one side, a small kitchen and the room of the hospital nun and, on the other, a bathroom and space for cleaning supplies. During construction, Domènech modified its orientation, rotating it 180 degrees from what was planned in the initial project so that the entrance faced the interior of the complex and integrated better with the overall circulation. The exterior decoration stands out for the high-quality ceramic mosaics adorning the side façades, depicting Saint George slaying the dragon and Saint Martin dividing his cloak, the work of Mario Maragliano. The pavilion, which was initially named Saint Joseph Oriol, adopted its current dedication in 1929. Over time, its original function was modified and the building was used for other purposes. Today, it forms part of the heritage complex declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is a singular example of Domènech’s ability to combine functionality with modernist beauty.

The Sant Jordi Pavilion of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner, is one of the two observation pavilions built during the first phase of the modernist project, funded by Pau Gil’s legacy. Located in the men’s sector, behind the Administration Pavilion, where the complex was accessed, the building was conceived to disinfect, isolate, and observe patients before they were transferred to a nursing pavilion, with special attention to the detection of infectious diseases. Smaller in size than the other nursing pavilions, it had a single floor with direct access from the gardens. The main body contained four individual rooms arranged along an open gallery that ensured natural light and ventilation. At the ends, the side wings housed, on one side, a small kitchen and the room of the hospital nun and, on the other, a bathroom and space for cleaning supplies. During construction, Domènech modified its orientation, rotating it 180 degrees from what was planned in the initial project so that the entrance faced the interior of the complex and integrated better with the overall circulation. The exterior decoration stands out for the high-quality ceramic mosaics adorning the side façades, depicting Saint George slaying the dragon and Saint Martin dividing his cloak, the work of Mario Maragliano. The pavilion, which was initially named Saint Joseph Oriol, adopted its current dedication in 1929. Over time, its original function was modified and the building was used for other purposes. Today, it forms part of the heritage complex declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is a singular example of Domènech’s ability to combine functionality with modernist beauty. -

Operations Pavilion of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau

The Operations House of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner, is one of the most distinctive buildings in the modernist complex, conceived to centralise surgical activity and ensure maximum hygiene and efficiency. It forms part of the first construction phase, funded thanks to the legacy of the banker Pau Gil, who made possible the creation of one of the most advanced hospitals of its time. The building occupies a strategic position along the central axis of the site, between the surgical nursing pavilions to which it provided direct service. It is structured over three floors and a semi-basement, with a characteristic volume dominated by large windows and the central tribune projecting from the main façade. The ground floor housed the anaesthesia and sterilisation areas, while the first floor contained the secondary operating theatres, and the second floor, medical photography and radiology laboratories, along with water sterilisation equipment. The main operating theatre, located on the ground floor, stood out for its glass roof that allowed abundant natural light, an innovative criterion inspired by international models. The rooms were lined with white tiles and easily washable surfaces, and the pavilion was connected to the underground network of service galleries for transporting materials and supplies. The main façade is a splendid example of modernist language. The entrance portico, with brick arches and carved stone, is decorated with two angels by Pau Gargallo and a raised tribune that incorporates sculptures by Eusebi Arnau and a ceramic frieze that pays tribute to the most distinguished surgeons in Catalonia’s history. At the top, the angel with outstretched hands by Arnau also stands out, symbolising protection and benevolence. The whole ensemble is completed with tracery windows and ornamental details that combine ceramics and mosaics with an austere elegance characteristic of hospital architecture. Surgical activity continued here until 2009, when it was moved to the new hospital. Throughout its history, the Operations House has been greatly modified to adapt to the healthcare needs of each period, yet it has retained its essential configuration and its presence as one of the key elements of Domènech i Montaner’s legacy at the Sant Pau Art Nouveau Site.

The Operations House of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, designed by Lluís Domènech i Montaner, is one of the most distinctive buildings in the modernist complex, conceived to centralise surgical activity and ensure maximum hygiene and efficiency. It forms part of the first construction phase, funded thanks to the legacy of the banker Pau Gil, who made possible the creation of one of the most advanced hospitals of its time. The building occupies a strategic position along the central axis of the site, between the surgical nursing pavilions to which it provided direct service. It is structured over three floors and a semi-basement, with a characteristic volume dominated by large windows and the central tribune projecting from the main façade. The ground floor housed the anaesthesia and sterilisation areas, while the first floor contained the secondary operating theatres, and the second floor, medical photography and radiology laboratories, along with water sterilisation equipment. The main operating theatre, located on the ground floor, stood out for its glass roof that allowed abundant natural light, an innovative criterion inspired by international models. The rooms were lined with white tiles and easily washable surfaces, and the pavilion was connected to the underground network of service galleries for transporting materials and supplies. The main façade is a splendid example of modernist language. The entrance portico, with brick arches and carved stone, is decorated with two angels by Pau Gargallo and a raised tribune that incorporates sculptures by Eusebi Arnau and a ceramic frieze that pays tribute to the most distinguished surgeons in Catalonia’s history. At the top, the angel with outstretched hands by Arnau also stands out, symbolising protection and benevolence. The whole ensemble is completed with tracery windows and ornamental details that combine ceramics and mosaics with an austere elegance characteristic of hospital architecture. Surgical activity continued here until 2009, when it was moved to the new hospital. Throughout its history, the Operations House has been greatly modified to adapt to the healthcare needs of each period, yet it has retained its essential configuration and its presence as one of the key elements of Domènech i Montaner’s legacy at the Sant Pau Art Nouveau Site. -

1910 - 1912

About

In this first stage, the catalogue focuses on the modern and contemporary architecture designed and built between 1832 –year of construction of the first industrial chimney in Barcelona that we establish as the beginning of modernity– until today.

The project is born to make the architecture more accessible both to professionals and to the citizens through a website that is going to be updated and extended. Contemporary works of greater general interest will be incorporated, always with a necessary historical perspective, while gradually adding works from our past, with the ambitious objective of understanding a greater documented period.

The collection feeds from multiple sources, mainly from the generosity of architectural and photographic studios, as well as the large amount of excellent historical and reference editorial projects, such as architectural guides, magazines, monographs and other publications. It also takes into consideration all the reference sources from the various branches and associated entities with the COAC and other collaborating entities related to the architectural and design fields, in its maximum spectrum.

Special mention should be made of the incorporation of vast documentation from the COAC Historical Archive which, thanks to its documental richness, provides a large amount of valuable –and in some cases unpublished– graphic documentation.

The rigour and criteria for selection of the works has been stablished by a Documental Commission, formed by the COAC’s Culture Spokesperson, the director of the COAC Historical Archive, the directors of the COAC Digital Archive, and professionals and other external experts from all the territorial sections that look after to offer a transversal view of the current and past architectural landscape around the territory.

The determination of this project is to become the largest digital collection about Catalan architecture; a key tool of exemplar information and documentation about architecture, which turns into a local and international referent, for the way to explain and show the architectural heritage of a territory.

About us

Directors:

2019-2026 Aureli Mora i Omar OrnaqueDocumental Commission:

2019-2026 Ramon Faura Carolina B. Garcia Eduard Callís Francesc Rafat Pau Albert Antoni López Daufí Joan Falgueras Mercè Bosch Jaume Farreny Anton Pàmies Juan Manuel Zaguirre Josep Ferrando Gemma Ferré Inés de Rivera Fernando Marzá Moisés Puente Aureli Mora Omar OrnaqueCollaborators:

2019-2026 Lluis Andreu Sergi Ballester Marianela Pla Maria Jesús Quintero Lucía M. Villodres Montse ViuExternal Collaborators:

2019-2026 Helena Cepeda Inès MartinelWith the support of:

Generalitat de Catalunya. Departament de CulturaCollaborating Entities:

ArquinFADFundació Mies van der Rohe

Fundación DOCOMOMO Ibérico

Basílica de la Sagrada Família

Museu del Disseny de Barcelona

Fomento

AMB

EINA Centre Universitari de Disseny i Art de Barcelona

IEFC

Fundació Domènench Montaner.

ETSAB

Suggestion box

Request the image

We kindly invite you to help us improve the dissemination of Catalan architecture through this space. Here you can propose works and provide or amend information on authors, photographers and their work, along with adding comments. The Documentary Commission will analyze all data. Please do only fill in the fields you deem necessary to add or amend the information.

The Arxiu Històric del Col·legi d'Arquitectes de Catalunya is one of the most important documentation centers in Europe, which houses the professional collections of more than 180 architects whose work is fundamental to understanding the history of Catalan architecture. By filling this form, you can request digital copies of the documents for which the Arxiu Històric del Col·legi d'Arquitectes de Catalunya manages the exploitation of the author's rights, as well as those in the public domain. Once the application has been made, the Arxiu Històric del Col·legi d'Arquitectes de Catalunya will send you an approximate budget, which varies in terms of each use and purpose.